The Best Hunter Safety Training

If experience is the best teacher, there’s probably nowhere in the world where it’d be better to take hunter safety training than Michigan.

Veteran hunter safety instructor Larry Martin shows his granddaughter Tracie how to sight a firearm.

|

Among Michigan’s coterie of volunteer hunter safety instructors, more than 130 of them have 30 years or more of experience. And that translates into many thousands of safe hunters.

“The commitment of 30 years to one employer is impressive,” said Sgt. Tom Wanless, who coordinates hunter safety with the Department of Natural Resources’ Law Enforcement Division. “Committing that many years as an unpaid volunteer is just phenomenal.”

Eighty-one-year-old Cloyse Lundie has been teaching hunter safety for 46 years. A long-time competitive shotgunner, sporting goods dealer and – before he retired last fall – range officer at Rose Lake Shooting Range for the DNR, Lundie started teaching hunter safety in 1967. Over the years, Lundie said he’s changed his style somewhat, and he thinks some of the newer techniques he’s adopted are better.

“I’ve gone to home study and I found that to be the best because they read that book from cover to cover,” said Lundie, who recently completed a class at the Durand Sportsmen’s Club. “When I had the three-day hunter safety class, I found that if I got three people with 100 percent score (on the written test), I was really lucky. Now, with 30 to 35 students, I get 15 to 20 of them with perfect scores. They come to class completely prepared. The kids come in knowledgeable and they don’t get bored. “The home study is really the way to go.”

When he first started, Lundie did his classroom work at schools (in three school districts and a private Christian school). “I must have put thousands and thousands of kids through the program,” he said. “Right now the kids that I taught are coming in with their grandkids.”

Classes are smaller than they were back in the day, Lundie said. He had 45 students this year; in years past, he had as many as 75 students in one school. “In those days, some of the physical education teachers would put hunter safety in their curriculum,” Lundie recalled. “Back when we had more pheasants, we had more kids. I used to have 30 to 40 boys and about three gals. Now I’ll have 45 in this class and half of them will be females – that’s the big difference, we have more females and more mothers involved.”

Lundie’s experience – seeing increasing numbers of females – is fairly common, other instructors say. “When I first started, if I had one girl in the class I was thrilled to death,” said Victor Ouellette, a retired police officer from Gaylord who’s been a certified hunter safety instructor for 32 years. “Now there are more girls and women than boys or men.”

There are also more adults taking the class. “It’s geared for 10- to 12-year-olds but a lot of parents don’t mind sitting through that class,” Ouellette said. “It’s not drudgery.”

Ouellette said modern technology helps keep the material fresh. “When I started, you had a film strip and a script and while you showed the film you read from the script,” he recalled.

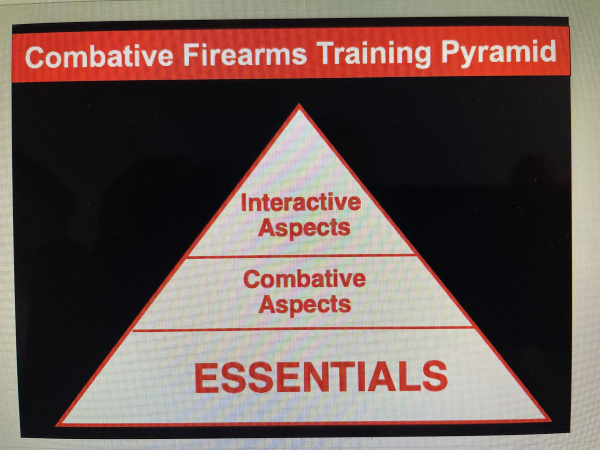

Ouellette said that when his presentation started getting stale, he had the filmstrip cut into slides, put the slides in carousel, and had a local radio announcer record the script. He’s moved on to video, PowerPoints and Internet presentations.

“Now the kids in Iron Mountain are getting the same information as the kids in Gaylord or anywhere else in Michigan,” he said, “They’re being taught in the same manner throughout the state of Michigan.”

Ouellette said his experiences as a police officer – including investigating shooting accidents – were what inspired him to teach hunter education. “I saw too many people, many of them youngsters, making stupid mistakes,” he said. “Education’s the answer, whether you’re dealing with vehicles, firearms, whatever.”

Larry Martin, 78, has been teaching hunter education since 1963, but he didn’t become a certified instructor until 1971. “I graduated from MSU and was taking a shooting class myself, so I set up a class for kids, 12- to 14-year-olds,” said Martin, who’s retired from the meat-packing industry. “Last year we had 114 students in the class at Ovid-Elsie High School. We teach 10 hours of class work – we always do it the second week of school – and then we go to Sleepy Hollow Sportsmen’s Club for the field work.

“I try to tell them what it was like when I was a boy. When we lived on the farm, we’d come home from school, the shotgun was standing in the corner and we’d just get the dog and go hunting,” he said. “In those days it was a big part of our life.”

Kids are busier these days Martin said, but those who come to hunter education are just as excited about hunting as ever. And he’s just as excited about teaching.

“It’s still fun,” he said. “When I see that student break their first clay pigeon – and we make them shoot until they break a clay pigeon – I get a kick out of it. It’s hard work; we’re really tired at the end of that day, but it’s well worth it.”

Seventy-year-old John Bell of Grand Blanc said he was involved with his local shooting club when “I stuck my nose in it” 31 years ago.

‘When I first started, most of the youngsters that took it were from hunting families,” said Bell, a General Motors retiree. “Now we have a lot kids who aren’t, but are interested, and a lot are from single-parent families with a mother who has custody. They don’t have the background. They still have the same enthusiasm, they’re just not coming to us with the same experience.”

Bell said he’s seeing more youngsters with special needs. When he was approached by the parents of a deaf youngster, he took it as a challenge. “I found an (American Sign Language) interpreter and put together a program for hearing-impaired people, and then a program for youngsters with various disabilities,” he said. “It’s probably the most rewarding experience I ever had in hunter education. We’ve never turned away a student because of a disability.”

Most of the DNR’s veteran volunteer instructors would like to continue for another 30 years. “I have no plans to quit instructing,” said Paul Hayes, an 82-year-old retired automotive worker from Flushing who’s been teaching for 41 years. “It’s enjoyable and it’s fun to see the kids, who want to learn, blossom. It always makes my day.” Said Bell: “They’re going have to dynamite me out of this program.”

The DNR has no plans to run anyone off. ‘The knowledge and experience these instructors have is priceless,” said Wanless. “They are a major contributing factor to Michigan’s safe hunting. “We appreciate all these men and women have done. The service they have provided to the citizens of our state and the Department of Natural Resources is invaluable.”