Michigan DNR Battling Grass Carp in Lake Erie Basin

Talk to anyone familiar with Michigan’s invasive species and you’re likely to hear their concern about carp – voracious, prolific, invasive carp.

News of electric barriers and fish flying into boats by the dozens may sound like a big fish story.

However, while they are sizable creatures, there is nothing exaggerated about the ecological and environmental damage that would occur if bighead and silver carp were ever to enter the Great Lakes.

Therefore, a good deal of attention is being paid to the work done by researchers and biologists in the Great Lakes states and Canada to help stop invasive bighead and silver carp from moving through the Chicago Area Waterway System toward Lake Michigan.

In addition to this ongoing work in Lake Michigan and its tributaries, Michigan Department of Natural Resources Fisheries Division staff and researchers are also focused on the problem of grass carp in the Lake Erie Basin.

Distinctions

Small numbers of grass carp have been caught in the Great Lakes and its tributaries since the 1980’s.

While bighead and silver carp are believed to have escaped from aquaculture ponds, grass carp were stocked intentionally in water bodies throughout many states for the purpose of aquatic plant control.

Since the mid-1980s, grass carp used in this manner were required to be sterilized so that they could not reproduce. However, periodic captures of fertile – or diploid – grass carp and the discovery of grass carp eggs in the Sandusky River in 2015 suggest that either the methods used to sterilize these fish were not always effective or compliance with state regulations barring fish able to reproduce was not complete.

It is illegal to possess or stock grass carp in Michigan. However, sterile – or triploid – grass carp may still be used for stocking water bodies in Ohio, Indiana, Pennsylvania and New York.

Though similar to silver and bighead carp in their breeding and habitat requirements, grass carp are different in two very important ways.

Michigan Department of Natural Resources fisheries biologist Cleyo Harris makes an incision into the stomach cavity of a grass carp for tagging.Grass carp feed exclusively on plants, whereas bighead and silver carp devour large quantities of plankton – the same food source required by native and sport fish species. In large numbers, grass carp can cause significant damage to wetland ecosystems and waterfowl habitat.

Unlike silver carp, grass carp do not jump out of the water at the sound of boat motors.

Varied research approach

Invasive species management is most effective at the early stages of an infestation, before a species becomes established.

The Michigan and Ohio Departments of Natural Resources have launched a collaborative research effort with Michigan State University and Central Michigan University to better understand the situation posed by grass carp in Lake Erie to then develop effective management measures.

In 2014, grant funding provided to Michigan through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative was awarded to Central Michigan University and Michigan State University to study the biology and behaviors of grass carp, with the ultimate goal of working towards eradicating these invasive fish from the Great Lakes.

Under the management of lead coordinator Seth Herbst with the Michigan DNR, Central Michigan University researchers are studying the fertility, diet and origins of grass carp captured in western Lake Erie.

Michigan State University researchers are evaluating large-scale movement, seasonal tributary use and migratory patterns of grass carp.

Herbst and other DNR staff from Michigan and Ohio are aiding in study design, collecting samples, and acting as liaisons between the commercial fishing industry and university investigators.

According to Herbst, this research is a first step toward the ultimate goal of eradicating grass carp.

“If eradication is not possible, the next goal is to use research information to develop and implement more effective control strategies,” Herbst said.

The research itself is being conducted by Travis Brenden, associate professor in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife at MSU, and Andrew Mahon, associate professor of biology at CMU.

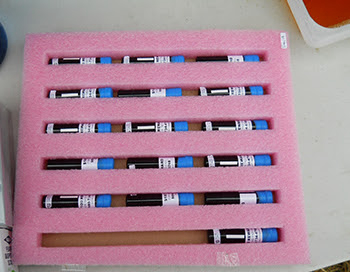

Brenden is studying the movement of grass carp in western Lake Erie by use of acoustic telemetry transmitters. According to Brenden, these transmitters are electronic tags that are surgically inserted into the belly cavity of the fish.

“Every 2 to 3 minutes, the transmitters emit a series of pings unique to each fish,” Brenden said. “The pings are detected and data including date, time and approximate location are recorded by receivers placed at different locations in Lake Erie.”

Brenden said one thing discovered, even with the limited results so far, is that these carp move farther than researchers thought they would.

“One fish that we detected in the Sandusky River in Ohio was originally tagged near Monroe, Michigan,” Brenden said. “Before being detected in the Sandusky River, that fish was detected north of Pelee Island, Ontario. The overall straight-line distance of this movement was close to 100 kilometers (62 miles).”

The location estimate of these pings lies within a small radius, as the signals are typically only detectible if a fish is within 1 kilometer of the receiver. That makes these findings both conclusive and surprising.

To some, another surprise might be the fact that these fish are permitted to move around the lakes at all.

“It may seem strange that we are releasing grass carp back into Lake Erie rather than just killing all the fish that are captured,” Brenden said.

“However, these tagged fish are providing a better understanding of migratory patterns that will allow management agencies to more effectively and efficiently exert control efforts.”

While Brenden focuses on telemetry to track movement, Mahon is hard at work studying the genetic, genomic, and fertility – or ploidy – status of grass carp.

“We’re finding that the large majority of grass carp are diploid, which is not a good thing,” Mahon said. “However, it is good that we are able to provide these data for management groups to use in their response to the invasion of these harmful fish.”

For this project, Mahon and his students are using some of the latest molecular technology.

“It is a great opportunity for me to train students and have them interact with the agencies that they may be working with in their future careers,” Mahon said. “And it gives me the excuse to be able to use some pretty amazing molecular tools.”

That suite of tools includes digital technology to screen water samples for environmental DNA, which can indicate the presence or absence of grass carp.

“For our reproductive tests, we’re conducting ploidy analyses by screening grass carp blood samples via light microscopy,” Mahon said. “Lastly, we are using some genomic methods to examine population structure of grass carp from the regions where we are able to capture and collect samples.”

Outlook

When asked about the future of Lake Erie, Mahon and Brenden agreed that it is still too early to predict the potential severity of the issue, as so much depends on the feasibility and success of control or eradication methods.

“It’s better to be proactive rather than reactive,” Mahon said. “And Seth Herbst is a leader when it comes to making sure Michigan is in front of this issue and preventing these fish from spreading any more than they already have.”

Get more information on invasive species, including carp, at www.michigan.gov/invasives.