Why Indians are Allowed to Gillnet Salmon

The rivers of the northwest once all belonged to local tribes to fish as they wished, and there were so few of them and so many fish that what they took had no impact on stocks.

That’s assuredly not the case now. From 2014 to 2019, the fisheries were so poor that the Commerce Department last year declared a fisheries disaster for much of the Pacific Coast, including the tribal fisheries in multiple rivers.

Now, with dams, urban and agricultural water use, pollution and reduced water flows in most years due to reduced snow pack and sea lion predation as well as offshore commercial harvest along with limited recreational harvest, many of the salmon runs (but not all) are a shadow of what they were once and there’s concern among anglers that the tribes continue to use gear which captures many of the salmon that make it into the rivers in short order.

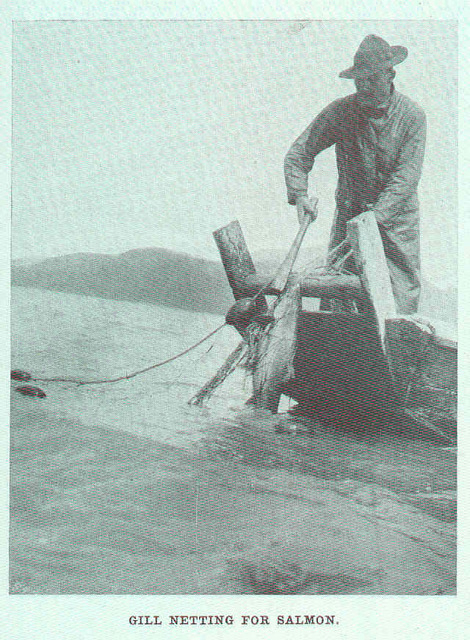

Why are the tribes permitted to use gill nets for the salmon when these nets have been outlawed for gamefish throughout most of the country?

First, the tribes finance and operate their own hatcheries, and stock some 40 million salmon annually in most years. That’s out of a total of roughly 250 million stocked each year including state and federal agencies. While the majority of these fish don’t make it to adulthood, many do, supporting both the commercial and recreational fisheries severely impacted by the dams on all of the major Pacific Coast rivers.

With that good comes some bad, unfortunately. Researchers are now discovering that hatchery fish are surviving to reach the spawning grounds, and their genetics are causing the remaining wild hybrids to have fewer traits that allow them to survive. The massive stocking, if continued, will likely mean an end to runs of wild fish.

Some biologists say that even the most severe fisheries restrictions, such as allowing no fisheries, commercial, sport or tribal, have failed to restore wild salmon runs because habitat degradation is occurring faster than we can reduce or eliminate fisheries. Even if all fishing were ended everywhere today, some runs would still become extinct simply because their habitat has been destroyed or degraded or cold water flow has been reduced to the point that it can no longer sustain them.

The areas where tribes continue to net are on salmon runs that are still abundant due to varying habitat needs and timing of their runs. While kings or Chinook have become increasingly rare everywhere, other species like some runs of chum and pink salmon appear to be thriving. These are the runs that the tribes harvest for the most part, though there is some incidental catch of other species.

Under federal treaties that have been in place for decades, the tribes and states each get a 50 percent share of the harvestable number of salmon available, as determined each year by joint meetings of biologists.

Native Americans say that tribes are forced by treaty to fish in particular areas. Because they can’t move their fisheries to focus on certain healthy runs, they bear an unequal burden in the effort to protect weak wild stocks. If returns are low to a particular tribe’s usual and accustomed area, that tribe won’t fish. They point out that sport fishers, however, are allowed to fish throughout the region, focusing their efforts on healthy runs.

Each treaty Indian tribe in western Washington maintains a monitoring staff that samples salmon caught in the fisheries. Every salmon is also reported on a fish ticket and the catch data is compiled and shared on a same-day basis with the state co-managers. Compared to sport catches, which are estimated based on catch record cards reported months later by individual fishermen, tribal fisheries report their catches more rapidly and more accurately, allowing in-season changes where needed to keep the harvest within established limits.

Bottom line is that though the tribal fisheries do capture a lot of salmon, they are not near to being the root of the problem in the declining cold-water fisheries of the northwest.

— Frank Sargeant

Frankmako1@gmail.com