MSU Research Shows Emerald Ash Borer Threatening Tree Species Vital to Indigenous Cultures

New Michigan State University research details how the emerald ash borer (EAB), an invasive forest pest native to Asia, is jeopardizing the entire U.S. and Canadian native range of black ash trees. The finding is particularly troubling because the trees are of cultural importance to Indigenous and First Nations groups.

Research results were published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. The effort was co-led by Nathan Siegert, forest entomologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service, and Deborah McCullough, professor in the MSU departments of Entomology and Forestry. The USDA Forest Service provided funding for the project.

Additional authors include:

- Thomas Luther, GIS analyst with the USDA Forest Service.

- Susan Crocker, research forester with the USDA Forest Service.

- Les Benedict, assistant director of the Environment Division with the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe.

- Kelly Church, fifth-generation black ash basket maker with the Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Tribe.

- John Banks, retired director of natural resources with the Penobscot Nation.

EAB was first discovered in southeast Michigan and southern Ontario in 2002. Since then, researchers say it has become the most devastating forest insect to invade North America.

McCullough is one of the world’s foremost experts on the pest and has studied its effects on ash forests for more than two decades.

“Adult beetles nibble on ash leaves but cause little damage. Larval feeding beneath the bark, however, is the real problem,” she said. “This invader pest has already killed hundreds of millions of ash trees in the U.S. and Canada, which is a problem ecologically and economically, of course. But black ash is unique. It usually grows in swampy or boggy forests, where few other trees can survive. It is also a highly valued cultural resource for many Indigenous tribes in the eastern U.S. and Canada that have used black ash trees for generations for basket making and other purposes.”

Female EAB beetles lay eggs on the bark of ash trees during the summer. Eggs hatch within two weeks and the larvae — the immature grub-like stage — burrow through the bark. Larvae feed in tunnels called galleries on the inner bark, damaging the ability of the tree to transport nutrients and water. Large limbs, and eventually the entire tree, die.

Black ash is more vulnerable to EAB than any other ash species in North America or Asia. Studies at MSU have shown beetles strongly prefer to feed and lay eggs on black ash compared with other ash species, and black ash trees die at lower larval densities than other ash trees of the same size.

Scientists have found that dead or dying black ash trees rarely produce viable stump or root sprouts, and endemic EAB populations and competition from other trees renders the survival potential of black ash saplings and seedlings in the region questionable.

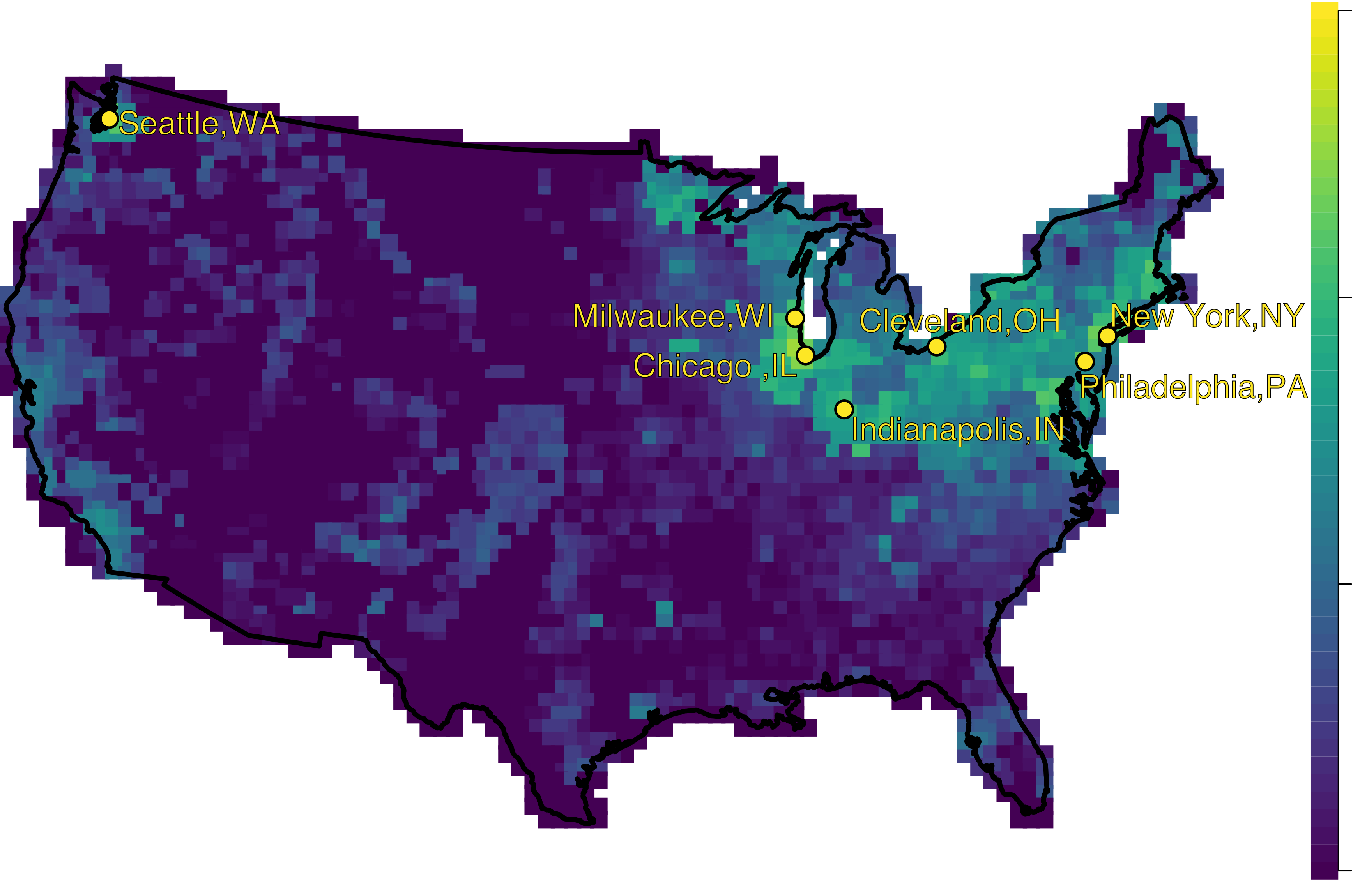

For this project, researchers used EAB distribution and spread in the U.S. and Canada from 2002 to 2020 to predict future expansion. Two different scenarios were modeled: one that assumed EAB would continue to spread at the same rate observed from 2002 to 2020, and another factoring in management that would reduce annual spread by half.

As of 2020, EAB had invaded nearly 60% of the native range of black ash, spreading at roughly 50 kilometers (about 31 miles) per year. Based on projected expansion, McCullough and her colleagues estimate that more than 75% of black ash basal area — used by scientists to describe the density and size of trees in a given area — will be lost across 87% of the species’ range by 2035 under both scenarios. By 2040, EAB will likely have killed all or nearly all overstory black ash across its native range.

For the Indigenous groups that use black ash for traditional basket making, tremendous urgency is needed to address the problem. To gain a greater understanding of the possible cultural effects, researchers identified Indigenous groups located within the black ash’s range and used U.S. census data to quantify Native populations in the affected area.

They found that 98% of the Indigenous people in the black ash native range will experience the loss of at least 75% of basal area by 2035.

“Black ash basket making traditions have been practiced since before this country existed,” said Church, a nationally renowned basket maker. “Educating the public about EAB and the potential for invasive pests like this, as well as collecting seed from live black ash and other native ash species, and replanting a variety of native trees, will be needed to help ensure we have healthy trees for future generations.”

Current methods to combat the dispersal of the insect have been largely unsuccessful, but McCullough said there is hope. Effective insecticides that are injected into the base of trees are available and can protect trees from EAB for three years. These injections can be coupled with girdling — killing the tree without felling it. Girdled trees act as traps in that they attract EAB adults to the treated trees, ideally reducing the growth of the EAB population in the area.

Public outreach efforts have led to fewer people transporting firewood, McCullough said, but EAB will continue to spread due to mature female beetles who can fly substantial distances.

Biological control releases — native parasitoids from Asia distributed in areas of North America — have occurred in numerous locations, but the acceptance of this practice varies across cultures and the efficacy has been tenuous.

Indigenous groups are employing a strategy to protect harvested black ash logs from EAB, other insects and decay by submerging them in water. The characteristics required for basket making are retained with this practice.

“Black ash is extremely vulnerable to EAB, more so than any other ash species,” McCullough said. “Our results show that over the next 20 to 25 years, the invasion will encompass virtually the entire native range of black ash in North America. It’s going to take a collaborative effort among scientists, Indigenous experts and resource managers to preserve black ash resources as best we can.”