Reverse Engineering a Failed Shot Afield

By Glen Wunderlich

Charter Member Professional Outdoor Media Association (POMA)

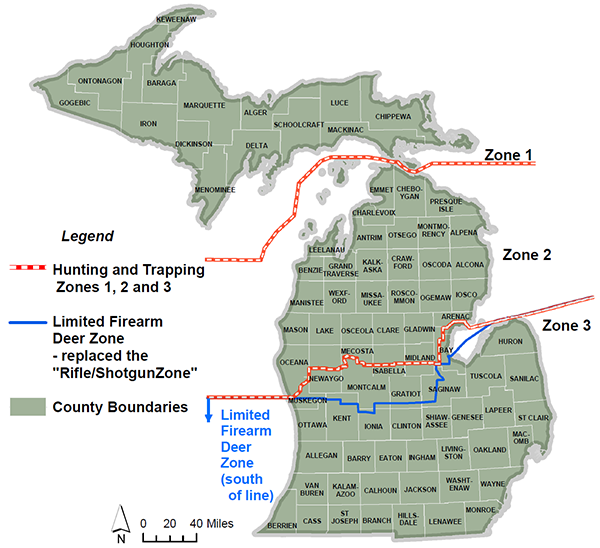

Muzzleloading deer season is open statewide through December 10th, but hunters in the southern Lower Peninsula have the option to use centerfire rifles with certain, legal straight-wall cartridges. Those in the northern Lower Peninsula and Upper Peninsula must use only muzzleloading firearms.

Here is one account of a hunt gone badly during regular firearms deer season.

My good pal, Joe, let me know he would be deer hunting for an afternoon sit during the regular firearms deer season, I was glad to hear it. Since I had been down with COVID-19, I was content to dogwatch his enthusiastic deer tracker, Junior. Well before sunset came the unmistakable sound of a single gunfire, followed by a two-way radio confirmation that Joe had knocked one down. The trouble began when the deer got to its feet and ran off.

Unfortunately, we never recovered the animal, as hard as the three of us tried. What follows is not meant to kick my good friend when he’s down, but rather an attempt to reverse-engineer the results of a bad shot that we must assume hit too high.

Mistake number one: When sighting in, Joe’s initial group was a bit high at 100 yards. He finished the sight-in session with a single shot 1 ¾ inches high – perfect for his Ruger American rifle in .450 Bushmaster caliber. However, we had not confirmed the center of a final group, because it was not fired after a final scope adjustment.

Maybe it was the high cost of ammo at $2 per pop. Maybe it was the accurate nature of the rifle/ammo combo, but that single shot left room for error.

Mistake number two: The reason for sighting in somewhat high at 100 yards is to maximize point-blank range. The rationale is to be able to aim at the center of the target without holding over or under within a given maximum range. Because the whitetail buck was confirmed to be at 145 yards, Joe may have subconsciously aimed a bit high to compensate for the bullet’s drop in trajectory.

Mistake number three: When I asked Joe where the crosshairs were when the gun went boom, he couldn’t answer conclusively. Although seemingly inconsequential, it is not. There is no bull’s eye attached to a deer, yet it is imperative to define an exact aiming point – the epitome of aim small, miss small theory.

Mistake number four: It was assumed that the velocity of Joe’s rifle/ammo matched the velocity printed on the box of Hornady ammo. The issue is that Hornady’s published velocity of 2200 feet-per-second with the 250-grain Flex-Tip bullet is the result of firing through a test barrel of 20 inches, whereas the Ruger’s barrel is a mere 16.1 inches in length. Without the use of a chronograph to measure actual velocity, it can be assumed that the Ruger rifle would produce substantially less speed than the longer test barrel. A most sensible option to verify trajectory at various ranges is to actually shoot at different ranges in practice; we did neither.

These are all avoidable errors easily overcome with more time at the practice bench. Certainly, big-bore deer guns are not particularly enjoyable to shoot with their heavy recoil and noise. Plus, the high cost of all ammo may shorten practice sessions. However, the consequences for shortcuts can linger well beyond the time it would have taken to check all the boxes of readiness.