Europeans Approve of Trophy Hunting

By Glen Wunderlich

Charter Member Professional Outdoor Media Association (POMA)

In a survey published in 2021 by the Humane Society International (HSI), it was claimed that Europe-wide opposition to “trophy” hunting existed based on its own study. Given an obvious emphasis on any negative aspects of big game hunting in the survey, there was concern that public opinion would be shaped by a limited understanding of hunting related beneficial activities.

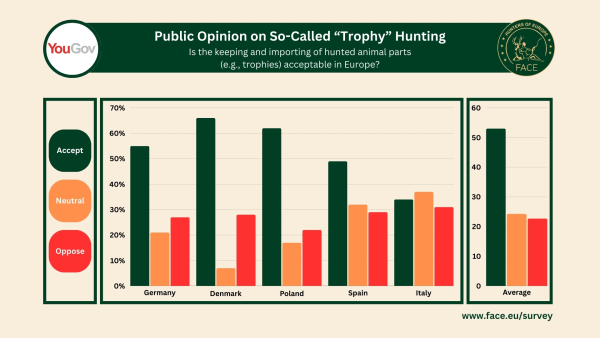

Consequently, a coalition of international sustainable-use organizations has commissioned a recent survey by YouGov that has unveiled a significant acceptance of international hunting, as evidenced by the 77 percent approval or neutrality of more than 7,000 Europeans from five countries on the matter. Therefore, a closer look into the various aspects of hunting big game in Europe is necessary to fully understand its impact, because there is quite a discrepancy in the two surveys.

From the Humane Society of the U.S. (HSUS), the picture is painted, as follows based on its website language: The hunters’ primary motivation is not to get food, but simply to obtain animal parts (heads, hides or claws and even the whole animal) for display.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume HSUS is correct.

But, what about the undisclosed consequences apart from any primary motives?

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) briefing paper, states that “trophy hunting…can and does generate critically needed incentives and revenue for government, private and community landowners to maintain and restore wildlife as a land use and to carry out conservation actions”

The survey, conducted in November 2023, aimed to determine unbiased public opinion on the social acceptance of domestic and international hunting. A focus was on the retention of animal parts (e.g. horns, antlers, etc.), as well as the acceptance of hunting that benefits conservation.

These findings challenge a narrow perception of hunting as solely targeting “trophies” of charismatic species often propagated by animal-rights organizations.

The promotion of bans or restrictions on the movement of legally obtained “trophies” are not supported by society, and doing so negatively impacts local communities, economies, and biodiversity.

One representative example demonstrates the disparity between HSI-think and the opinions of the combined countries of Italy, Denmark, Poland, Spain and Germany from the YouGov survey: whether it is acceptable for parts of legally hunted animals to be kept and imported, if legal and regulated. YouGov acceptance was 53.2 percent compared to HSI at 7.4 percent. YouGov opposition came in at 22.8 percent yet HSI opposed the same question at the rate of 84.4 percent.

In conclusion, well-managed trophy hunting can bring in much needed income, jobs, and other economic and social benefits to indigenous and local communities in places where these benefits are often scarce. The injection of cash to these poor people is welcome relief and is used to further conservation of their wildlife and to improve sustainable livelihoods.

Often it is pointed out that tourism can also provide income apart from hunting; however, it is quite limited because access is needed along with supporting infrastructure. It also requires guaranteed wildlife viewing opportunities, which are often complicated with a lack of political stability – all conditions where trophy hunting takes place. By partnering hunting with viewing, the puzzle pieces begin to fit into place.

Nowhere is there mention of a single species worldwide that has become unsustainable as part of well-regulated and managed hunting for one simple reason: It has never happened.

The nature of humans behooves them to manage any business to ensure its long-term survival. Comprehensive wildlife management is no different no matter where one looks.