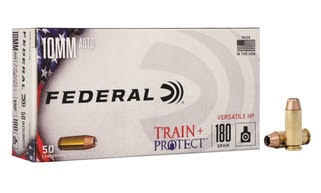

Federal Ammunition Adds New Train + Protect 10mm Ammo

ANOKA, MN – Federal recently added a new line extension to its popular and versatile Train + Protect product line—which features packaging that honors any shooter’s birthright to bear arms—with a new load in 10mm Auto. The full-power 10mm offering features a Versatile Hollow Point (VHP) bullet to deliver both precise, practical performance at the range, and instant, reliable expansion on impact.

Train + Protect | Federal Ammunition (federalpremium.com)

“With the popularity of our Train +Protect products and customers desire to have a good all-around option they can use for training as well as protection, we’re expanding the line with 10mm auto,” said Federal’s Handgun Product Line Director Nick Sachse. “10mm has seen a resurgence in recent years and we continue to receive requests for more options in the cartridge.”

Summary of features include: New 180-grain 10mm Auto load; VHP bullets based on proven Federal versatile hollow-point design; Reloadable Federal brass case; Extremely reliable primer; Loaded to produce consistent performance on the range and in defense situations; 50-count boxes; MSRP: $57.99. Read more